Model Behavior

stock motions, modeling environments, and fantasies of standardization

Say hello to model Kate.

I made model Kate in a software called Metahumans, for a project I’ve been working on called Gestural Publics, which will ultimately become a dance performance yielding a public, online motion archive. The piece is about stock choreographies, and about AI models, and about models in general—including how models get trained, what a model simulates, and what kinds of fantasies (ideologies)1 are embedded in these simulations.

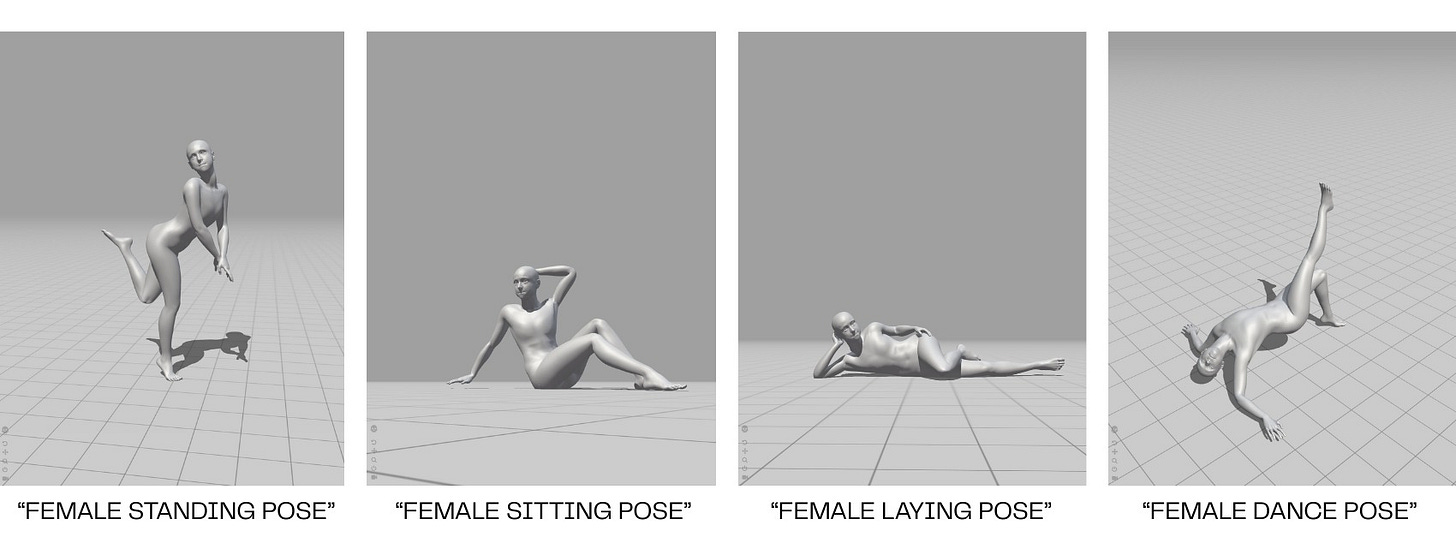

Stock motions are banal, generic clips of motion capture that you can download and use for 3d animation and game development. They’re the motion capture equivalent of stock photography. There’s a specific library I’ve grown attached to called Mixamo, and with Mixamo, I can make model Kate do all kinds of things:

Mixamo is a product from Adobe, whose business is built on a suite of industry-standard products for creativity and design. Like most platform assets, Mixamo’s library enables creation while standardizing movement vocabularies. I view assets like these as choreographies, because they design or organize the motions of the body and its expressive capacities to create a sense of meaning. As such they carry their fantasies (ideologies) with them, and those are technical as well as formal. One of the fantasies (ideologies) suggested by stock motion is that any body can do any motion. So, model Kate can do all these moves, but so can this zombie, and this mannequin, and this mouse, and this grandma, and this humanoid, who is also, unfortunately, named Kate.

Mixamo makes this very easy, smooth, and frictionless—on their interface, it happens in just a few clicks. With a few more steps (well documented for the general public on Youtube tutorials), these motions and bodies can be transported into animation and gaming software.

These cute little moves on campy avatars seems pretty funny, but it’s important to note that we can also make model Kate do culturally specific movement forms like jazz dance, and Capoeira, and twerking.

I (live Kate) have very little direct, embodied experience with these movement traditions. I haven’t worked with their actual histories and resonances. I have not been conditioned by the ideologies, imaginaries, and/or resistances contained by their movements and bodily comportments. But there’s model Kate, doing these moves oh-so-accurately—or, at least as accurately as the unnamed and uncredited “professional motion actors”2 who recorded these movements for Mixamo. All this to say: Mixamo presents some ethical and positional tensions with replication and representation.

But recall, Mixamo is for everybody! So luckily, there are movements from Mixamo that I do have training in.

Thanks, Mixamo. I feel *so* represented.

Creating and Embodying Digital Choreographies

When I was learning to animate, I started a little practice of making little dances and animation experiments out of Mixamo moves. I kept noting their seductive qualities - they can be funny, they can be impressive, they can be sickening, they can even be beautiful. However, they maintain some qualitative similarities: eerie exactness, no relationship to weight or weightedness, and moments of stillness or transitional immediacy that feel outside of reality.

I got curious about embodying these digital qualities, so I started teaching myself to perform live the dances that I programmed digitally. I quickly learned that replicating these digitized motions, even those originally performed by humans, even (gendered) ones that I have been trained to embody, is extremely difficult. This simple action of learning to perform stock motion disrupts its underlying fantasy: that any body can do any motion and it’s smooth, and easy, and frictionless.

Modeling Environments

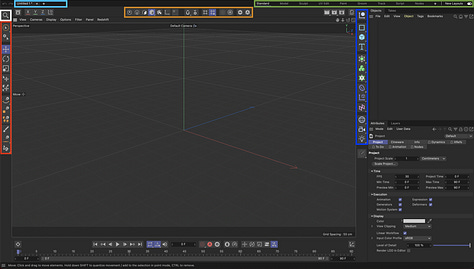

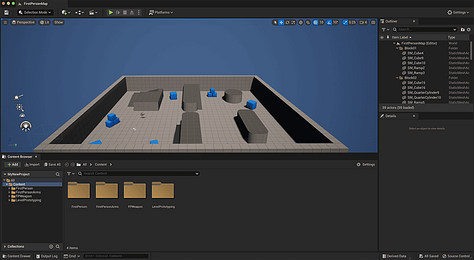

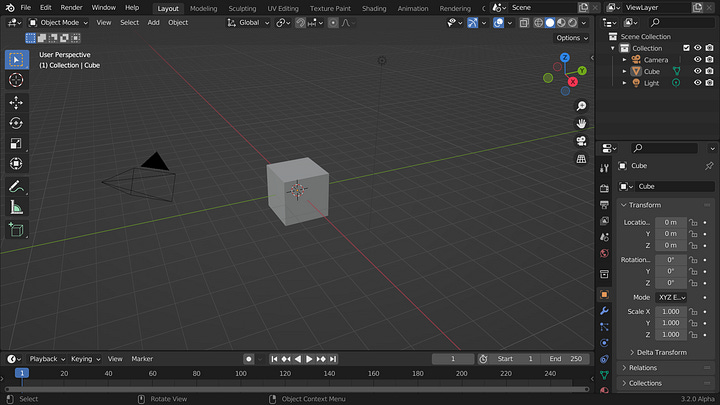

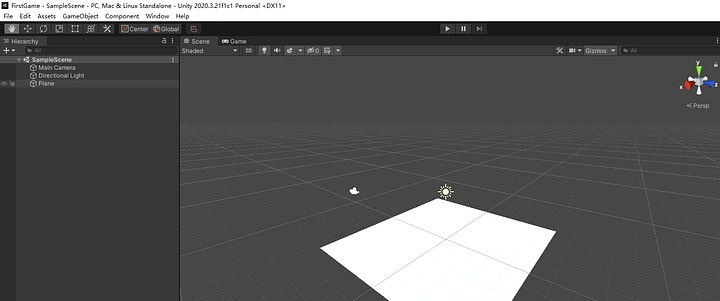

Moving away from the motions themselves, let’s address the software that motion gets animated in. From the images above, you’re familiar with the Mixamo interface: isolated bodies in segmented grey voids, who perform their moves on grey grids that extend forever into the horizon. Now let’s take a look at other 3d animation programs.

It’s all a grey void, that a creator populates with grey objects, that resemble modeling clay. Again, these aesthetics hold fantasies, or ideologies: ones of transformation, of moldability, that anything could become anything else; that any place could be anywhere else. Modeling spaces hold a similar fantasy as the movements that get programmed and sequenced within them. Modeling environments display and endless void, a placeless space,3 where any body can do any thing and any thing can become anything else. It’s all smooth, frictionless clay in the hands of a creator.

Of course bodies and objects in these spaces don’t stay gray clay forever—they become textured, more lifelike. They attempt to simulate the real. Art and digital culture critic Nora Khan notes that such simulations are usually superficial:

That modeling capacity, to have no limit on represented diversity, is a subtle and seductive trick. This world can have wildly diverse-looking, designed bodies, with the maker choosing from skins swatches and hair textures and body templates, creating a whole brilliant palette of ages, ethnicities, genders, orientations, weights, and heights…but what that difference actually means—how it activates, how race affects access to opportunity and resources, how these wildly different “ethnic packs” influence social dynamics—are not factored into the game’s procedural framework. Each body model has fluid mechanics, normative movements, and they slot easily into the game’s own guiding mechanics. They eat, they walk, they speak and understand each other; they move from home, to work, to play, to work. We might consider what imbibing this perfect representation of difference without activation of what that difference means as it is lived in the world, does to our understanding of the “real world” when we head back out to it. Clue: Gamergate.

— Nora Khan, Seeing, Naming, Knowing

I’m persuaded by Khan’s point about difference and its role (or lack thereof) in simulation. When difference is shown in high fidelity but has no meaningful effect on behavior, Khan suggests that people come to expect the same smooth, frictionless experience outside of digital frames. When that fantasy (ideology) is inevitably disrupted by those who are different, they are met with anger, disdain, or even violence.

Making difference matter

The world, and thus worldview, presented by stock motions is one of sameness: standardized bodies tirelessly replicating standardized motions through digital worlds formed and decorated by standardized objects and materials. Such standardizing practices claim to be representative of the totality of the ‘real’ world, but in actuality represent no one; instead, they represent a fantasy (ideology) that people move with frictionless ease and regularity. This has political implications: that a “normal” body is compliant, controllable, and predictable. Stock motions present choreographic simulations of live bodies, and in circulating as choreographic material, they reproduce the normative patterns they encode. Gestural Publics seeks to make these patterns tangible and embodied, and to intervene in their formal and technical fantasies through choreographic practice.

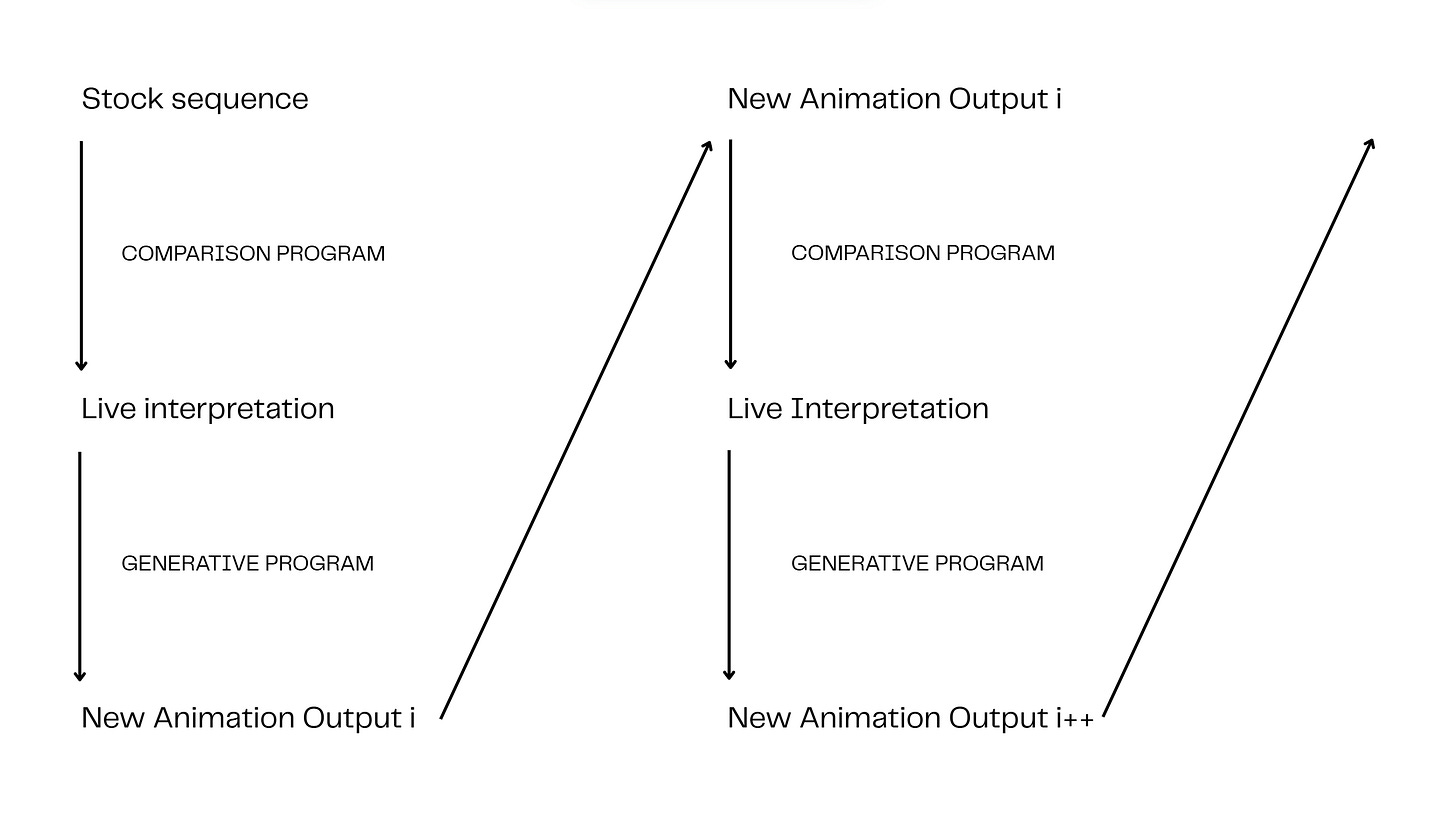

Instead of giving in to stock motions’ role in perpetuating standardization and frictionless replicability, what I’m trying to do with Gestural Publics is surface the impossibility of sameness, as revealed by the live body trying and failing to conform. I’m trying to make difference matter, and because I am annoyingly literal, I’m making the computationally analyzed difference between a stock animation and a live interpretation the parameters for its transformation.

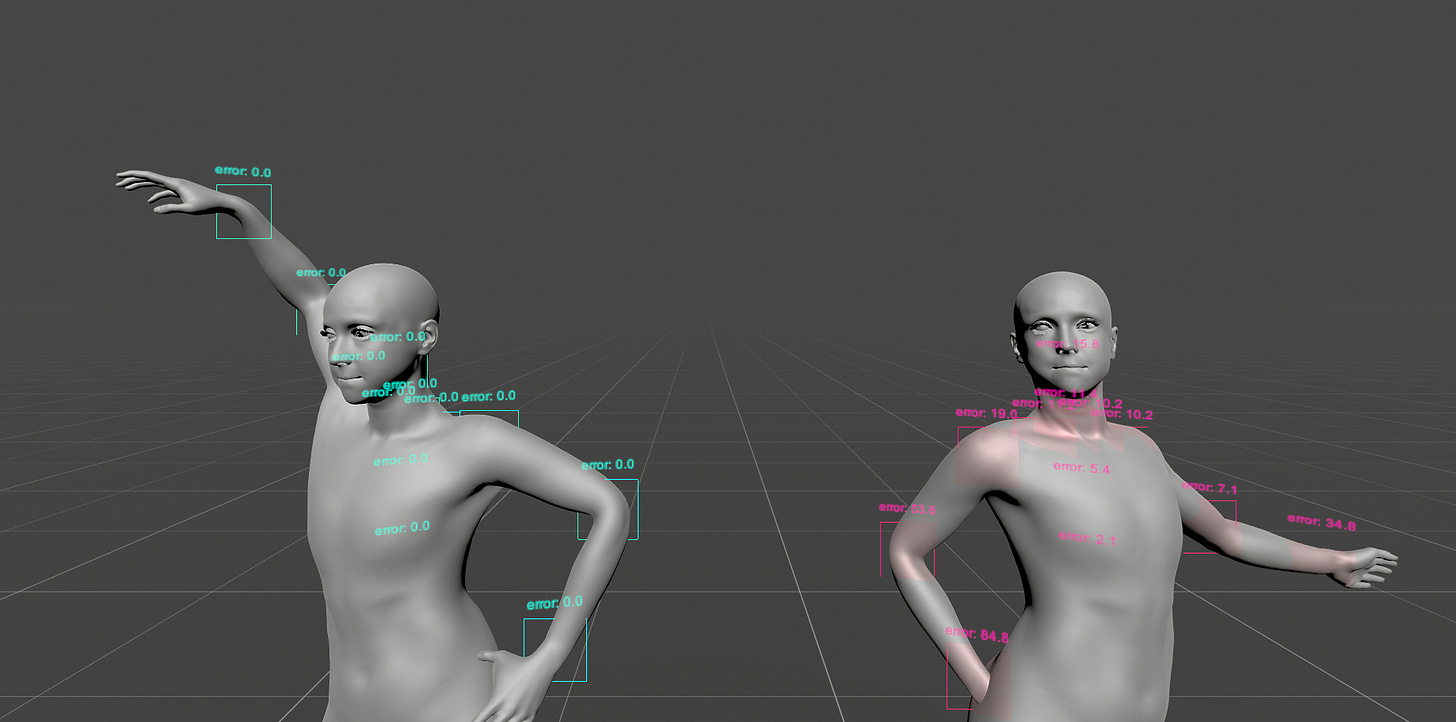

This system isn’t operational (yet!), but I’ve been running concurrent experiments, looking for ways to visualize the difference between the stock phrases and the dancer’s deviations from them.

The above video compares the bone positions and rotations of each avatar; the color of the line that connects them changes depending on how similar the avatar’s rotation and position are to each other.

Finally, the last video looks for versions of motion that deviate the most from the stock motions, watches them for a few seconds, and then moves on to the next most different version.4 It also renames the motions - from what Mixamo suggests (usually something like “female dance pose”) to a lexicon developed during rehearsals.

These experiments are progress, but they are ultimately insufficient. Surfacing difference is something computers are already very good at.5 Transformation, however, is difficult, despite what fantasies of standardization, conglomeration, and frictionless replication might tempt us into believing. What is required for difference to matter procedurally, not just cosmetically? Colleagues recently reminded me that the perceived failures of the work hold their own poetics. If the system keeps pressing the body toward an impossible ideal, maybe the pressure can be repurposed—so that in the gap, a counter-ideal can quietly take form.

Gestural Publics will have a first showing during the Ammerman Center 18th Triennial on Arts + Technology, March 26-28, 2026. See you there?

Nodding here to Sydney Skybetter, who deepened my understanding of how and why the aesthetic is always ideological in his excellent lecture, Clock, Fall.

This is how Adobe credits the originators of this movement on their website. Lenovo further elaborates: “Animations are generated from a vast database of pre-recorded human motions, covering a wide range of activities. While motion capture data is not directly used by Mixamo, it simulates motion-capture style animation by extracting key poses and blending them.” So, it would seem Mixamo animations are already algorithmically generated, one step removed from the performers’ data.

Via Susan Foster’s Knowing as Moving, I learned about the colonizing logic of “space” as opposed to “place.” Foster has reminded me of (and cited) the robust existing literature on this topic.

These motion capture takes are from Bree Breeden, MK Ford, and Peter Pattengill. They created versions of a stock motion sequence that deviate from the pose, but still maintain a relationship to it. This movement has become training data.

Simone Browne’s Dark Matters and Ruha Benjamin’s Race After Technology and Sasha Costanza-Chock’s Design Justice will tell you all about the disturbing aptitude of computational surveillance and profiling.